The following story involves a dear friend of mine who passed away from ALS. Jim and I shared many rock adventures including the building of his patio, though I must admit having had access to his serious back-hoe sure beat using a pry bar.

We have much to learn from Far East gardens, note I did not say Japanese Gardens. But did you know that the rage in Japan is for American and English styled gardens. We have successfully Ann Lovejoy-ed them. To think of some of those Shinto shrines being neighbor to some of our English Garden designs makes me shudder. I think we can and do learn from all sorts of insights and discoveries. Be it from a Shinto Shrine, the neighbor next door or from a Hurricane Ridge experience

If you go up into the high country you will most likely come across douglasia or seline acaulis— a cushion plant, one of the belly plants of nature. And it never seems to grow, or very seldom in an open scree. It usually finds its place next to a rock. First, because it gets a lot of survival energy—heat from the rock. And because the plant starts this way and then ventures out and the warmest part of the plant is in the center. It too will be the first part of the plant to die. You come and look at the plant and see the remaining circle of the green. But everything is still held in situ, but step on, or injure any part of the plant and within a year the whole plant may be gone. For a plant this small, it might take 25 years to grow.

It is respect and patience with plants that we have learned from the Far East and from their gardens. It is respect born of knowing when to be meticulous and caring. When you visit our High Country, you learn much from our native plants. I think that’s where I have learned the most – especially in rock work and design.

Jim wanted color in this garden, flowers and plants which I could supply. I wanted the rocks to be the focus. His wife agreed with me. “Could a garden be an area with no plants, but an arrangement of natural materials such as stones, rocks and timber?”

All too I often think of the garden as that place where weed buckets lay ever full and the pruning shears are always dull, and all that work … but somehow I think the definition should always include the place at the end of the day where you say “This is what I have, this is what I have done!”

A garden is about discovery and that can include all forms of materials. Were I to move to the desert, I would be tempted to make a dry stream bed. Not a Zen garden stream but one that would include all the wonderful rocks they have done there. Not like the river beach rocks we have in the Northwest but like the Bryce Canyon and all of those colors.

The gardening would be in the translating of those colors and moving them through that dry stream bed. Now, that would be a warm cozy garden for me. Rocks, that are not stopping stones to look at, but rocks that blend and flow and with every changing hour that bring new colors, new shadows.

Rock gardens do not need plants; but the lichen, the saxifrage and the moss simply invite themselves to heat gathering sources. In California I had to drive for hours to get to a high enough elevation to where plants were minimalized, where there was enough wind and winter snow to render trees into bonsai, growing stunted and picturesque. Here on the Olympic Peninsula I can be in this zone in an hour or so. In Asian gardens, the bonsai or Zen garden is often the most edited of gardens, every branch, and every rock carefully placed or trained.

I submit, that nature, left alone also edits, often very beautifully. Centuries ago Japanese gardens were influenced by the mainland (China and Korea), but the special attention to stones in the garden came from Shinto beliefs and the influence of Neolithic nature religions. The highly stylistic Japanese Garden that we know today is much more related to the influence of Buddhism, which came to Japan in 580.

Jim’s garden is situated on a slope, which drops west towards the Dungeness River. It is a masculine setting with the powerful sound of a raging river influencing all I attempt to do.

The main colors are the green tones of the trees and the slate blue of the river beneath. Light comes sparingly and fleetingly through the trees in this dark canyon setting. There is coldness to this garden, brought by the site itself and the temperature of this snow melt fed river. Winter and spring at this elevation is very cold and this garden will therefore be designed for being enjoyed in the warmer months of summer and fall.

Our winters are long and gray, so an attempt was made to provide for some spring relief in the use of hardy bulbs and sturdy dogwoods. Plants with tender blooms such as magnolia would be used only after careful selection, and it was my intent that no primary color would ever dominate. The various shades of green would be the main pages upon which this landscape would float, colors such as red would arrive in fall by means of the Katsura and the red weeping maple.

The use of native plants or hybrids thereof were planned to be of white and violet, for example, iris, bellflower, azalea. The exception being of the Kousa dogwood, which has dominance for only a short time, and will be tempered by the soft yellow of epemidium and white of hellebore.

I am sure that by summer I will find some patches that do not work. Will it be the Liriope leading to the bamboo? Only time will tell and a garden only grows by its mistakes. No garden can ever be finished – nor should it be. I only hope that this garden; be it entered from the south, from the river or from the deck always engages the visitors eye with thoughts both reflective of the inward garden as well as expanding the consciousness to the world outside.

[column] [/column]

[/column]

And Sometimes all good stories come to an end. (c) Herb Senft 2008

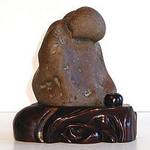

Will this be a meditation garden? I hope so. The illumination gathered from within this garden will not come from having used bright colors, but from the commitment and placement of these rocks, and the care and nurturing of the bonsai set within.

There is ‘spirit’ alive in all things, rocks simply move at a slower pace and to their eyes our quicksilver lives must register but lightly, if at all.